On an August morning in Mullaitivu, journalist Kanapathipillai Kumanan received a summons. It was from the Terrorism Investigation Division’s sub-station in Mullaitivu, instructing him to appear on the 17th. The summons didn’t say why.

For the past few months, Kumanan had been documenting the painstaking excavation at Chemmani — the infamous mass grave site tied to one of the most disturbing wartime allegations in Sri Lanka’s recent history. His reporting has been steady, deliberate, often confronting silence or hostility. Now, with human remains once again surfacing from Mullaitivu soil, the story that began in 1998 has returned to the national stage. And so has the unease that comes with it.

“Just a month after the Presidential election of 2024, the TID (Terrorism Investigation Division) visited me. They said they received a complaint. I’m working closely with Tamils facing issues such as disappearances and land issues, seeking international attention, that has been the complaint. So that’s why they started an investigation, they said” he recalled. According to Kumanan, he has been accused of creating conflict between the military and the Tamil people by providing media coverage on protests and agitations carried out in the North and East of Sri Lanka.

Kumanan knows the politics of intimidation well. “This government said before the election that they were against the PTA (Prevention of Terrorism Act is a highly controversial law which allows indefinite detention without charge). I understand that they need more time to repeal the PTA and introduce a new law. But I don’t want to see it used as a tool of harassment. So many youths who are activists, journalists… They are also questioned by TID. It’s the usual thing, a day to day thing,” Kumanan said.

In the ten months since President Anura Kumara Dissanayake took office, others in the North, East and even in the capital Colombo have faced similar summons, Kumanan said. The allegations vary — stickers supporting Palestine, comments on social media and general activism — but the tool is the same: the Prevention of Terrorism Act.

Asked if the PTA is being used under this government who campaigned heavily on repealing the law, Kumanan was unequivocal. “There’s no change. I only hope this government can understand that the PTA is an oppressive tool for minorities like me. But I’m wondering if they have also begun to misuse the PTA. That’s the real worry,” he said.

Kumanan’s worry captures the contradiction of this moment. Chemmani’s renewed excavation is a breakthrough — initiated by the state itself. Yet the mechanisms of control that have long stifled dissent remain in active use.

The PTA to be abolished in September

Addressing Parliament on Friday, Foreign Minister Vijitha Herath announced that the Prevention of Terrorism Act (PTA) will be abolished by September. He dismissed suggestions that the move followed pressure from the UN Human Rights Office, insisting it was a sovereign decision.

Herath defended the continued use of the PTA, arguing that it was not wielded against Tamil and Muslim minorities but rather “to target organised crime involving the underworld.” “If some were arrested under the PTA recently, the majority of them were Sinhalese,” he said, claiming links to drugs and underworld networks.

The Minister assured that a new law will replace the PTA. He also stressed that politically motivated abuses, including killings, journalist abductions, disappearances and the Easter Sunday investigation, would be addressed within Sri Lanka’s legal system, saying: “There will be no need for external intervention because our judiciary today has been strengthened.”

The government may promise repeal and replacement with a new law, but for those still living under the shadow of PTA — like Kumanan — confidence won’t come easy. Until the machinery of repression is dismantled, doubt will likely linger.

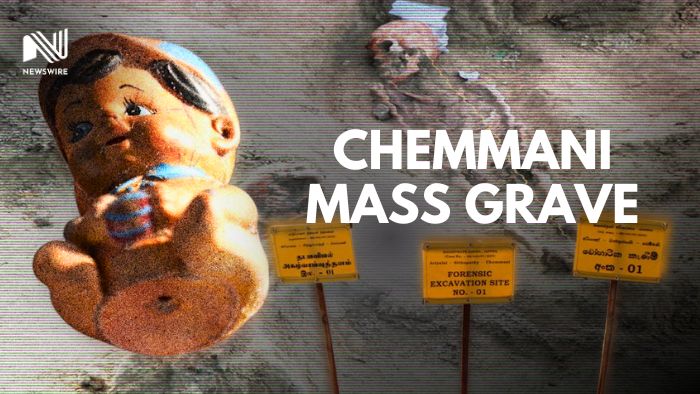

The weight of Chemmani

The Chemmani mass grave is not a vague wartime rumour. It is a documented site, with a paper trail, eyewitness testimony, named suspects, and direct links to a high-profile crime: the 1996 gang rape and murder of schoolgirl Krishanthi Kumaraswamy. In 1998, convicted Sri Lankan Army soldier Lance Corporal Somaratne Rajapakse alleged that the bodies of some 300 to 400 Tamil civilians lay buried there, killed during the army’s recapture of Jaffna from the terrorist outfit LTTE.

Initial excavations yielded 15 bodies. Only two were identified. The rest of the investigation was mired in political interference and silence. For 27 years, the site lay unmarked.

This year, in February, during renovations at a crematorium near the original site, human remains surfaced again. 147 human remains have been excavated so far, with the next phase of excavation due to resume. Unlike other mass graves, Chemmani comes with the possibility — and the danger — of implicating the chain of command. Rajapakse, still on death row, has said he is willing to testify before an international inquiry, claiming he can name senior officers.

For human rights lawyer Bhavani Fonseka, the significance of what is happening now lies in the fact that the process is moving — at least for the moment — without overt obstruction. “As far as we can see, what was clear is that the state actors who are conducting the excavations are able to carry out their functions without any problem as of present, and that the magistrate who is overseeing it is able to function in his capacity as having jurisdiction in that area,” she said recalling her recent visit to Chemmani.

These, she notes, are “positive signs”. But they exist alongside a sobering reality: “There is disappointing progress on the promises made. We have not yet seen what exactly the government is going to do with the promise to set up a public prosecutor’s office. We continue to see the use of the PTA to arrest and detain individuals, she said. Fonseka also noted of the custodial and encounter killings that have taken place under this government.

Slow burn system change

For political scientist Jayadeva Uyangoda, the pace of change under Dissanayake is deliberate, not deficient. “This government has started what many people would call a system change,” he said. System change was the call of the 2022 people’s movement ‘Aragalaya’ during the height of Sri Lanka’s economic crisis. And according to Uyangoda, the Dissanayake’s National People’s Power (NPP) is the only political party in Sri Lanka that had the potential and capacity to initiate this process. Other parties he believes are too fragmented to even attempt this.

“System change and transformation takes a lot of time. You cannot do it overnight, within a liberal, democratic, constitutional framework. If you work within the liberal constitutional framework, it has to be a slow process. That is what this government is doing.”

In his view, the NPP government is avoiding the “adventurism” that could trigger right-wing extreme reactions or conspiracies to unseat it. The pragmatism extends beyond domestic reform. “The opposition wanted the government to confront the International Monetary Fund, to adopt a confrontational strategy towards the United States and India as well. The government, particularly president Dissanayake, has very wisely avoided falling into these very unwise and shortsighted proposals.”

However, Chemmani, Uyangoda notes, is a rare example of the state initiating a politically risky process. “The excavations were initiated by the government — not by the opposition, civil society, or NGOs. We have to give the government credit for that. But there must also be a forensic inquiry, the identification of victims, and then the identification of the perpetrators. Was it the LTTE or the military? Who were the other actors? That too is a huge task. Yet the Chemmani issue is being narrowly politicised by the media and the opposition, and these fundamentally important questions are being trivialised,” he lamented.

Between promise and pushback

Bhavani Fonseka sees the months ahead as a test. September marks one year of the Dissanayake presidency. The UN Human Rights Council will take up Sri Lanka’s case, and the Office of the High Commissioner following the report on Sri Lanka released recently.

“It’s a big test, but there are signs that there may be a break from previous attempts at sabotage. The President in Parliament pushed back on those critiquing the recent arrest of a former navy commander. Hopefully that is an indicator that this government, this particular President, respects the rule of law and will let those processes move forward without political interference,” she said.

But she warns of nationalist “noise” that could derail progress, and points to concrete measures still missing.

Balancing diplomacy and domestic repair

Even as the government treads cautiously on accountability and civil liberties, its focus on stabilising the economy has produced more visible gains. Central Bank Governor Dr. Nandalal Weerasinghe is upbeat: “Once a country is hit with a crisis, it will take four to five years to come back to the same level to recover the output loss. In our case, within three years, we have almost reached there. Within the next year, Sri Lanka will exceed pre-crisis levels in key areas such as employment, poverty reduction, incomes, and cost of living,” he said in a televised interview.

His optimism is not unfounded. When the Trump-era tariffs were announced mid-year, few believed the NPP-led administration could secure a favourable outcome for Sri Lanka. Yet trade negotiations with the United States — expected by critics to falter — have instead delivered a reduction in tariffs on Sri Lankan exports to 20%. “In terms of comparison, we are better off compared to India and China, who have higher tariffs. There could be trade diversions happening, there will be better opportunities for our exporters,” Weerasinghe noted.

Finance Ministry Secretary Dr. Harshana Suriyapperuma framed the deal as part of a broader strategic goal: “The primary goal was to determine how Sri Lanka could move forward while preserving its competitive position in the regional market — not solely on the tariff percentage, but on maintaining market share for Sri Lankan exporters of goods and services,” he said announcing the deal earlier this month.

Yet behind these wins lies a harsher reality. Sri Lanka’s fiscal position remains under severe strain, with debt servicing costs consuming a disproportionate share of public finances. In the 2025 budget, LKR 2,950 billion — equivalent to 8.9% of GDP — has been allocated solely for interest payments on public debt.

This amount accounts for nearly 60% of the government’s total projected revenue of LKR 4,990 billion. By comparison, the combined revenue from key taxes — including VAT, Excise Tax, Social Security Contribution Levy, Withholding Tax, and PAYE — is estimated at LKR 2,860 billion, covering just 97% of the total interest bill.

This relentless debt burden leaves little fiscal space for essential services or development spending. The government faces the delicate task of balancing IMF-mandated fiscal consolidation with the urgent need for growth and social protection. High debt service obligations, combined with elevated poverty levels and heavier tax burdens on low-income households, underscore the complexity — and political risk — of steering the economy towards stability without deepening public hardship.

The one-year ledger

Taken together, these external wins and slow internal reforms offer a mixed first-year report card. In its first year, the Dissanayake government has opened a door no government since the war has dared touch: Chemmani. It has navigated complex trade talks to Sri Lanka’s advantage, steadied an economy many thought would take longer to revive, and avoided the foreign policy traps laid by a fragmented opposition. That recovery rests in no small part on the foundations laid by former president Ranil Wickremesinghe’s administration, which, to Sri Lanka’s fortune, handed over the reins respecting the people’s mandate. AKD, as the president is popularly known – without conceit, had maintained the reform agenda, recognising the country has little room to manoeuvre.

But his government has also left key reform promises unfulfilled, kept the Executive Presidency in play, and presided over incidents — from land appropriation moves to custodial deaths — that cast doubt on its willingness to confront entrenched abuses. This year has also seen a sharp rise in violent crime, with 80 shootings reported so far and 44 deaths, an uptick in underworld gang activity that has raised serious national security concerns and given Sri Lankans haunting reminders of a violent past.

Following Friday’s dramatic arrest and remand of former President Ranil Wickremesinghe, questions have also emerged over whether the AKD government is setting a dangerous precedent. Critics point to a perception of selective justice, with opposition parties uniting to frame the move as political vengeance and raising doubts about genuine accountability.

Uyangoda’s caution rings through: “This government is very different from all the other governments that we have known since 1948. They have to be in power for five years. So what they will do is slowly lay the conditions for a system change, without creating conditions for political uncertainty and hostile reactions of those who will be losing from this system change project.”

In other words, the arc is long. Whether it bends toward justice will depend not only on the patience of its architects, but on their courage to push past the point where pragmatism becomes paralysis.

And there will be losers. According to Uyangoda, they include powerful sections of society — the entrenched political elite and their networks, the business interests built on patronage, and segments of the media that thrived under transactional politics. For decades, these actors shaped the rules, narratives, and flow of resources to their advantage. This government, for all its caution, has begun to unsettle that equation.

It is, as Uyangoda notes, neither Marxist nor revolutionary. It is not the ideological experiment some expected either. Instead, it appears to be a pragmatic, progressive administration attempting system transformation within the parameters of the existing Constitution, the democratic process, and the rule of law. That pragmatism may be its greatest strength — or its most dangerous limitation. (Newswire)