When the 14th Dalai Lama first crossed the snowy threshold into India in 1959, he carried with him not only the anguish of a displaced nation but the spiritual lineage of a thousand years. India received him not as a refugee, but as a revered guest, an heir to a tradition that had once flourished in the very soil of Nalanda and Vikramashila.

Today, as the question of his reincarnation looms, India is no longer just a sanctuary. It is the crucible in which the future of Tibetan Buddhism and the moral authority of the Dalai Lama will be forged. India is not foreign to Tibetan Buddhism; it is its ancestral womb.

The teachings of the Buddha, the logic of Nagarjuna, the compassion of Asanga, all were born here. When Tibetan masters translated Indian texts into Tibetan, they were not importing a foreign religion; they were reclaiming a spiritual inheritance. In this sense, the Dalai Lama’s presence in India is not exile. It is return.

The next Dalai Lama, if born in India, would embody this continuity. He would be a child of both refuge and origin, nurtured in the land where the Dharma first bloomed. This would not only reaffirm the spiritual legitimacy of the institution but also deepen its philosophical roots. China has made its intentions clear: it seeks to control the reincarnation process, to install a Dalai Lama of its own choosing. But legitimacy cannot be manufactured.

It must be cultivated in the soil of trust, freedom, and spiritual authenticity. India, with its democratic ethos and constitutional protection of religious freedom, offers precisely that. By hosting the Tibetan government-in-exile and safeguarding the Dalai Lama’s teachings, India has become the de facto guardian of Tibetan spiritual sovereignty.

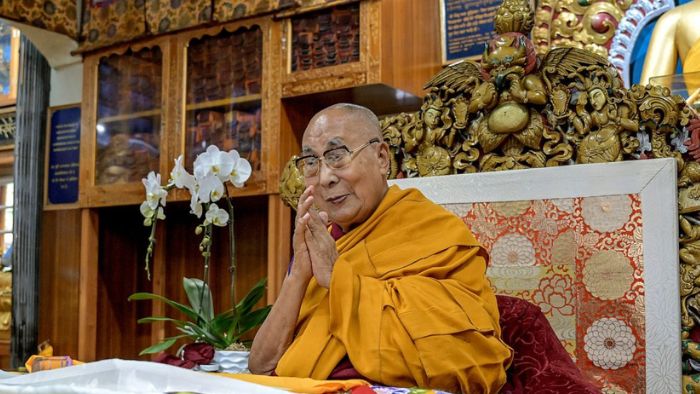

Should the next Dalai Lama be identified within India, it would send a clear message: that reincarnation is not a political tool, but a sacred tradition beyond the reach of authoritarian manipulation. India’s role is not merely logistical. It is moral. In a world fractured by identity politics and geopolitical rivalry, the Dalai Lama represents a rare voice of equanimity, compassion, and disciplined joy.

His teachings resonate far beyond Tibet or Buddhism; they speak to the human condition. India, by nurturing this voice, becomes more than a host; it becomes a steward of global conscience. The next Dalai Lama, raised in India’s pluralistic embrace, would inherit not only the wisdom of Tibet but the moral clarity of Gandhi, Ambedkar, and Tagore. He would be a bridge between worlds, a child of exile who teaches belonging.

India’s role in the next Dalai Lama is not to claim, but to protect. Not to direct, but to dignify. In doing so, it honors the sacred trust placed upon it by history, by the Tibetan people, and by the Dharma itself. The question is not whether India will play a pivotal role. It already is. The deeper question is whether it will continue to do so with the humility, courage, and compassion that the moment demands.