Hot dogs, bacon, a cool alcoholic beverage, and some nice hot sunlight sets the tone for a wholesome weekend morning or a nice Sunday afternoon barbeque. All of the above have been identified by the International Agency for Research on Cancer (‘IARC’) as group 1 carcinogens (including the smoke from the burning coal in the BBQ grill). Their peers in the same category include the likes of gamma-radiation, plutonium, formaldehyde, asbestos and tobacco.

Understandably, potentially cancer-causing consumables may attract discussions on whether restricting or (in some cases) prohibiting the product is appropriate. But surely a witch hunt against products that are not in any grouping of carcinogens should (at the very least) garner a second thought? How has nicotine – a substance that is not on any IARC list – become guilty by association?

In the late 2nd century AD, economic instability, military threats from bordering tribes and internal unrest threatened the stability of the Roman Empire. In response, Emperor Commodus decided that the best course of action to distract the public would be for him to engage in performative arena combat and commission statues of himself in heroic poses. In the aftermath of cyclone Ditwah and increasing global geopolitical tensions, certain earnest and overzealous policymakers and regulatory authorities have decided to engage in similar heroic posturing to direct public attention towards the ‘pressing’ issue of combatting tobacco and nicotine products.

Regardless of the dubious timing of these new efforts, the real defect lies in the framing of the problem. The first mistake is in trying to prosecute too many crimes in a single breath, ricocheting from physiological harms of smoking to air pollution, littered cigarettes butts and vaguely gestured-at threats to the ‘marine ecosystem’ from vaporizers, without ever pausing long enough to substantiate a single charge. In casting their net so wide with the hope that something will get caught, they’ve found themselves with a mesh so loose that their entire argument itself has slipped right through.

The second, and more fundamental issue is that the problem and the hypothetical solution both overextend themselves by carelessly conflating ‘smoking’ and ‘nicotine use’ and proposing stronger regulation of both ‘tobacco’ and ‘nicotine’, as if these things are interchangeable.

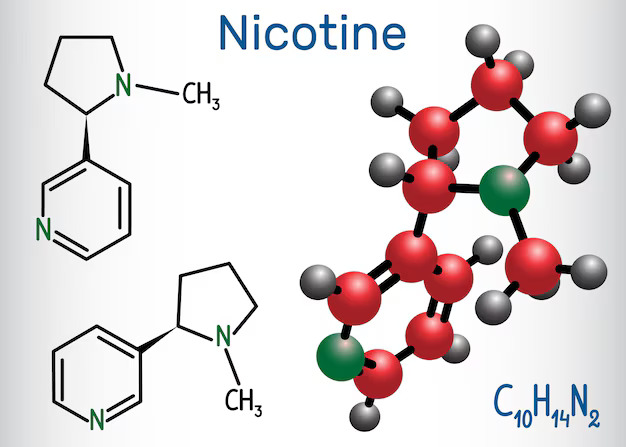

If the real concern is disease rather than decorum, then the villain in this narrative needs to be recast. Nicotine is without a doubt addictive. But so is caffeine and a host of other everyday consumables. Addiction is not the same as pathology, and it is not nicotine that earns tobacco its place among the usual suspects on the IARC’s most notorious list. The overwhelming majority of smoking-related diseases arise (instead) from the toxic cocktail produced by combustion – tar, carbon monoxide and thousands of other by-products released when tobacco is burned. This distinction is not semantic hair-splitting but settled science. The World Health Organization does not classify nicotine itself as carcinogenic. Both the UK National Health Service and the US Food and Drug Administration have been unambiguous that nicotine, while dependence-forming, does not cause cancer, heart disease, lung disease or stroke. It is the ‘smoke’ part of ‘smoking’ that does the killing.

Treating nicotine as the moral equivalent of asbestos or plutonium may make for a satisfying and simple narrative. But it collapses under even casual scientific scrutiny – and worse – it misdirects public health policy from actual, practical and viable mechanisms for tobacco harm reduction.

By- R. Perera